A photographic image is true and false in equal measure.

(Quote from Gerry Badger in The Genius of Photography, p.8). The earliest days of photography don’t bring any ideological foundation to its trajectory through history. The one thing you can’t do with a consideration of photography’s story is to call it The Story of Photography. Even in the 1830s, it was postmodern. There are, as Gerry Badger has pointed out, many stories of photography, and it proves impossible to ask them to form a neat line. As Fox Talbot so aptly showed in The Pencil of Nature (1844-46), even when you ask photographic images to show us what they can do, the multiplicity of the ‘picture-ness’ itself defies a confining logic.

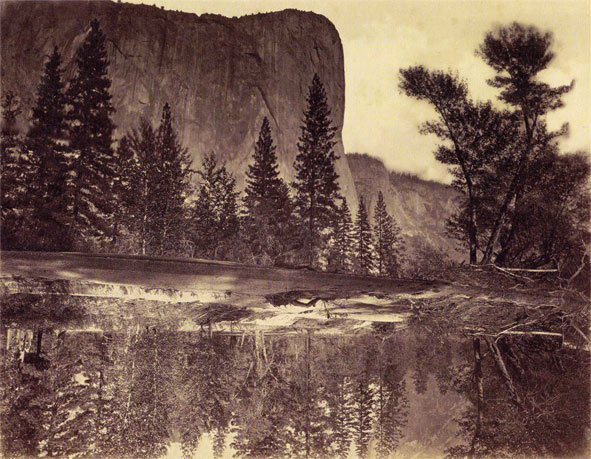

Talbot’s book is a series of commentary on 24 photographs (all originally unique calotypes), produced in instalments over two years. Architectural scenes, still life, copies of drawing and print, the textures of manmade and natural objects: an eclectic choice of subjects are all accompanied by short texts of description or reflection on the image-capture process. Ian Jeffrey has noted the uncertainty in this presentation of ‘the new Art’ (Talbot’s term used in his introductory outline of the process at the beginning of The Pencil of Nature), suggestive of the surprise at being made ‘acutely alert to seeing itself’ (p.26, Photography: A Concise History, 1989).

Fox Talbot remarks on the camera’s ability to see everything ‘all at once’ (after Plate III, Articles of China), to ‘introduce into our pictures a multitude of minute details which add to the truth and reality of the representation’, being found to ‘give an air of variety beyond expectation to the scene represented’ (after Plate X, The Haystack), to ‘awaken a train of thoughts and feelings, and picturesque imaginings’ (after Plate VI, The Open Door), to produce copies of any number of artefacts which ‘may be preserved from loss, and multiplied to any extent’ (after Plate XXIII, Hagar in the Desert), ‘as much larger or smaller than the originals as we may desire’ (after Plate XI, Copy of a Lithographic Print). He even muses on the possibility of the photographic image making visible the invisible, by virtue of fixing ultraviolet rays (after Plate VIII, A Scene in A Library).

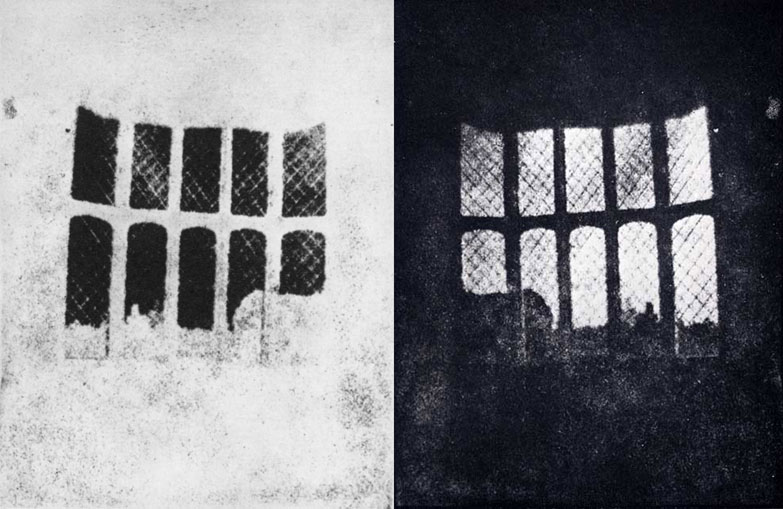

Each of these, and others besides, act not only to endorse the polyvalence of a photograph’s possible meaning, but also to present the paradox of photography: we both see the subject as immediate, as a short-circuit to visual reality AND we inhabit the interpretative process which is always invested in a picture, undermining such objectivity. Like Talbot’s first negative of 1835, above, this reveals that perceptive flip of comprehension, where the impossibility of operating in two modes at the same time is brought tantalisingly close. Close enough to explode the dominance of all previous means of representation.

Header image: Latticed Window, Lacock Abbey (negative and positive), 1835, by W. H. Fox Talbot.