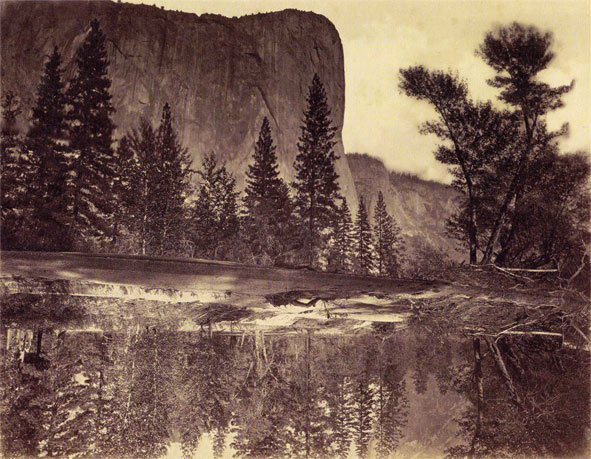

Muybridge: a 19th century, postmodern photographer. Comparing his work to that of his contemporary Carleton E. Watkins, Rebecca Solnit (with acknowledgement to Mark Klett’s remarks about the ‘composed’ modernism of Watkins’ photographs) writes:

Muybridge, even when photographing almost exactly the same subjects, could not be more different. In his sensibility, the world is all but discomposed, constantly in flux. Even something as solid as a government building reveals itself to be a creature of change; the water we think we know becomes eerily unfamiliar whether seen too slowly, as ghostly films, or too quickly, as leaping beasts; his late portraits are not portraits of human beings but of their actions, of movement itself; some of his landscapes, via their clouds, are really two different moments spliced together; and his panoramas often promise a single sweeping glance while actually being made up of several nonconsecutive moments. Even his taste in surfaces and textures runs to the intricate, elaborate, dense, and tangled: they are not smooth, stable, or easily deciphered. Finally, his tricksterish moments of subversion of the supposed truth or continuity of a given work of art render more uncertain and less stable the subject at hand.

(from Eadweard Muybridge, Philip Brookman, Tate Publishing, p.187). This is the prevailing reflection on Muybridge from all 5 contributing essays in the book – that he destabilises the picture plane, the norms of picture-making, the solidity of people and place, the assumptions of perception. His work is ‘an exercise in impossible seeing, transcending the bounds of ordinary human vision’ (Rebecca Solnit, p.185). Corey Keller notes the continuous interest in ‘effect’ (p.217), that specific attention to the format and display of images so prevalent in Victorian times which links the spectacular image with the bodily involvement of the viewer – through stereoscopy, his zoopraxiscope, and pull-out book panoramas (and may also include the presence and authentication of the creator himself). A similar theatricality is detected by Marta Braun in the composition and manipulation of the supposedly sequential images in Animal Locomotion, Muybridge’s seminal publication of 1887.

Perhaps this ‘mixing it up’ of image practice and publication, crossing art and science, is uncomfortable for today’s high art world because it seems like a muddying of the waters of a distilled, pure ideology of the photograph. Such an ideology does not exist. It’s like the clear, sharp, focussed presentation of a window on the world which turns out to be an upside-down reflection, a magical mirage. (Incidentally, the image above, on display in the 2010 exhibition in its original published album, is deliberately printed the ‘wrong’ way up among the sequence of mammoth plates. In the exhibition catalogue, it is ‘corrected’ by the Tate publishers and turned around.) There is, rather, a constant rupturing of any synthesized whole, and the suggestion instead of a subliminal turbulence and uncertainty about the world and the way we picture it: both in terms of individual images and in terms of Muybridge’s career as a whole.

Header image: Tutokanula. Valley of the Yosemite No. 11, 1872, Eadweard Muybridge.