In The Modern Public and Photography, part of a review of the Paris Salon’s 1859 exhibition, Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) wrote his famous diatribe against photography’s growing presence in the art world. Having first published on the occasion of the 1845 Salon, Baudelaire was now, as he wrote his last review, witnessing the first time that photography was included in the exhibition. If he was often a sharp and vocal challenger of the traditions of French academy painting, he was nevertheless a defender of the ideals of art as he saw them: beauty as both eternal form and essence of modernity (The Painter of Modern Life, published 1863, p.17 in Penguin Great Ideas). Photography, in his eyes, should only ever be the ‘handmaid of the arts and sciences’, ‘the secretary and record-keeper of whomsoever needs absolute material accuracy for professional reasons’ (p.110, 111).

Near the beginning of this short article, Baudelaire quotes Jesus’ words, “‘Oh, ye depraved and unbelieving race,’ says Our Lord, ‘how long must I remain with you, how long shall I continue to suffer?'” (p.105, quoting Matthew 17:17, Mark 9:19, Luke 9:41). The remainder of the essay then loads the terms of the argument with ‘faithless’ artists and public, ‘sun-worshippers’, whose ‘idolatrous multitude’ have a new credo (‘I believe in nature, and I believe only in nature. I believe that art is, and can only be, the exact reproduction of nature.’) and a new messiah – Daguerre (p.105, 108, 109). To our 21st-century ears, this not only seems overly dramatic, but casts the whole frame of photography’s technical accomplishments in paradoxical terms: on the one hand, there isn’t enough believing going on (in art and progress), and on the other hand, there is too much infatuated belief (in photography’s veracity). Has 150 years or so reversed this view?

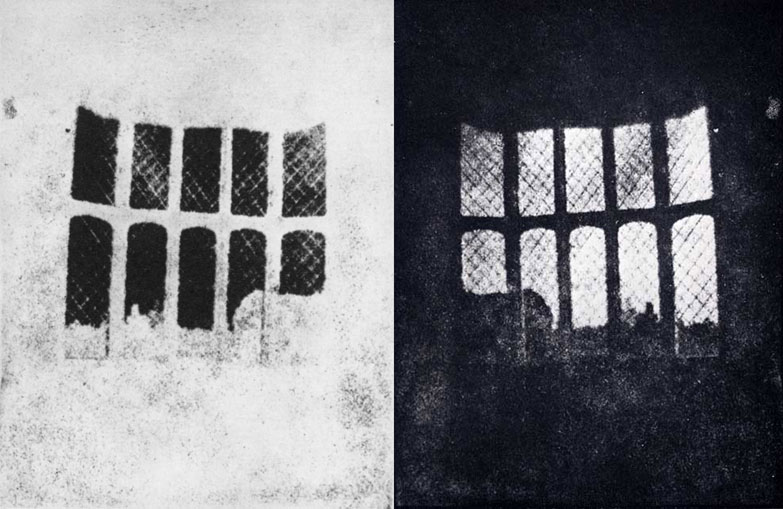

There had been public displays of photography prior to the Salon exhibition, initially at the Paris Expositions des produits de l’industrie in 1844 and 1849, but the techniques and equipment were part and parcel of displays then more concerned with the mechanics of the new process. Celebrated photographs held a more prominent position in the Great Exhibition at London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, arguably the first international open photography exhibition, and throughout the ’50s groups such as the Photographic Society of London and the Société française de photographie held their own displays (the above picture showing the first such exhibition in a museum). Photography was on the cusp of institutional definition that veered in two opposing directions – a tool for information-gathering or an expression of artistic vision.

Header image: Exhibition of the Photographic Society of London and the Société française de photographie at the South Kensington Museum, 1858, by Charles Thurston Thompson.