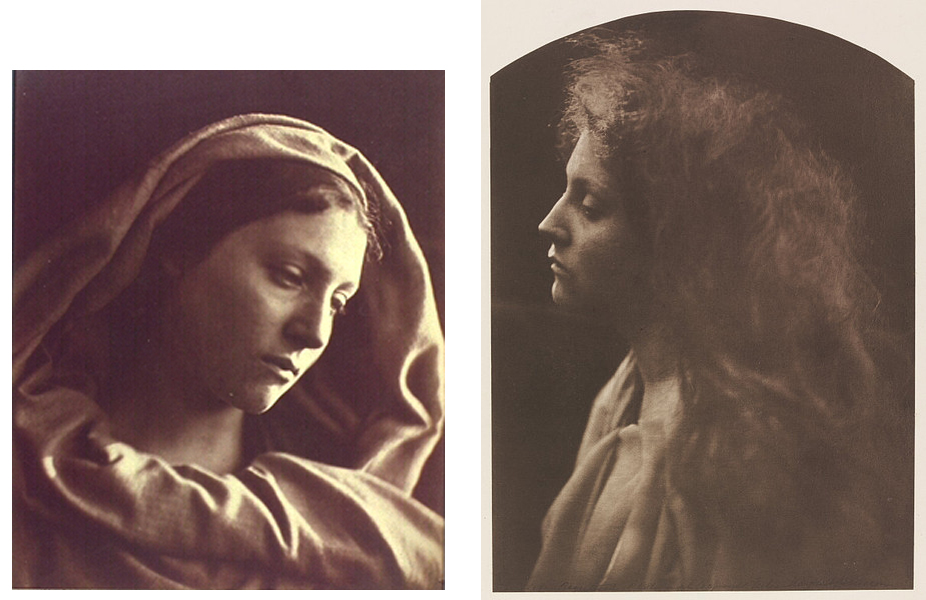

The Virgin Mary is a compelling and complex character for any believer, particularly a woman of the mid-nineteenth century. On the one hand, she was the ideal of femininity – gentle, nurturing, compassionate. If ever there was a woman who was great through love, it is the Madonna. On the other hand, as both mother and virgin, she presented a paradox. Because her virtue was reconciled with her motherhood through divine interventions, a method not available to other mortals, she represented an unattainable realm for women. … [Noting the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception proposed by the Catholic Church in 1854] If Mary is without original sin, she is not simply a mortal who has been blessed, but she is both human and divine, unique in her purity, and, as such, all the more daunting as a model of feminine grace.

—

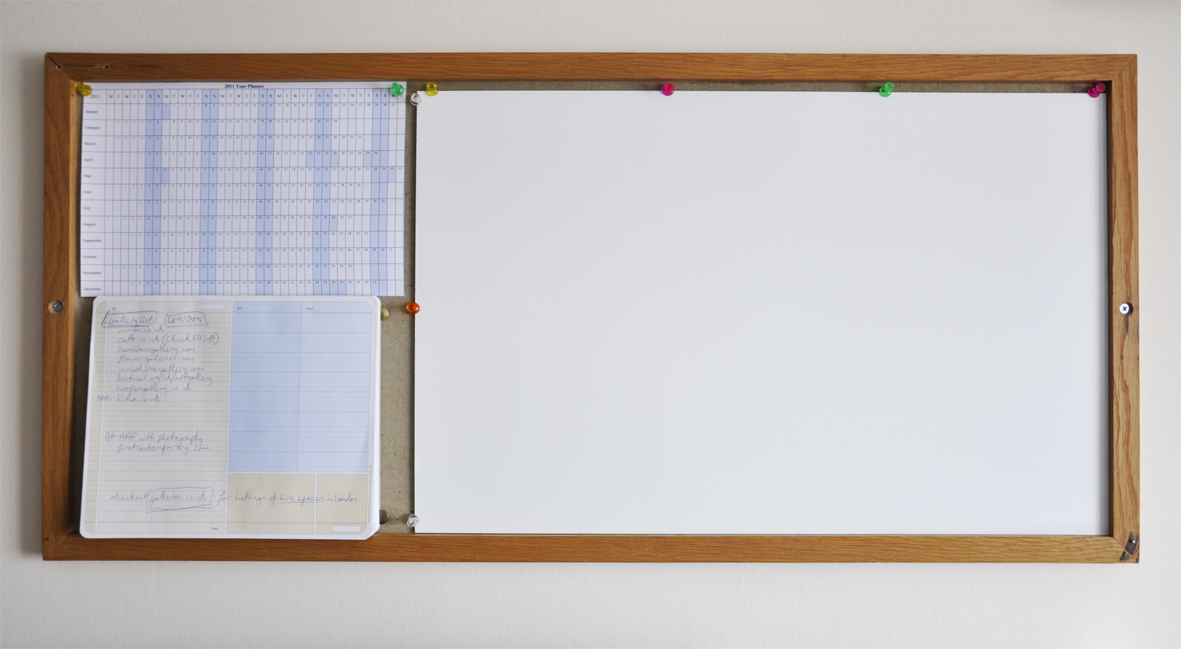

The photograph of The Angel at the Tomb takes as its subject the angel who was in attendance at the moment of Christ’s Resurrection. In the Scriptures, the angel is a man. In this photograph, the angel is Cameron’s maid Mary Hillier. Decidedly feminine, her profile is cut by a light from above that accentuates the delicate contour of her brow, nose and chin. Hillier’s hair is the dominant feature of the picture. rendered in soft contrast and orange-coloured tones, her cascade of kinky waves dissolves to cotton softness at the bottom of the frame. With a sheet wrapped around her shoulders and carelessly pinned just below the sternum, Hillier is slightly disheveled, a woman in dishabille. In fact, she looks more like Mary Magdalene. … The picture is of a woman who seems to be at once a heavenly figure and someone of flesh and blood – she is both melancholy and angelic, sensual and divine.

From Sylvia Wolf’s Julia Margaret Cameron’s Women, p. 62-63.

Header image: Mary Mother, 1867 and The Angel at the Tomb, 1870, by Julia Margaret Cameron.