David Mach’s exhibition (30 July – 16 October 2011, City Art Centre, Edinburgh) brings together a multitude of work on biblical themes, timed as it is to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the King James translation. There are over 40 pieces, of which 5 are sculptures and the remainder are predominantly large-scale photographic collages. The former occupy perhaps a more prescribed space for Christian reference, in the crucifixions and caricatures of Jesus and the devil, even though the materials (coat-hangers and matches) may diverge from familiar forms. The latter are infinitely more interesting for representing biblical scenes with more reference to contemporary idiom than traditional painting type.

It’s true to say that textual knowledge of Bible stories is not a commonplace, and Mach deliberately ploughs his way into the mythical status occupied by such stories. For him, the fact that what people (including himself) know of the references is often half-known, as if a memory or association, is important for being contemporary. It’s part of the practice of being an artist today; the only way to sing in tune, as Jean Cocteau would say, is to sing from one’s own genealogical tree. So the approach that might assume sincerity as the only credible alternative to an ironic, cynical or critical use of biblical imagery in contemporary art is proved false by Mach. He isn’t detached from the stories, but neither is he a faith-filled believer using the stories to express his religion.

This middle ground is what Richard Holloway, in his introduction to the catalogue, equates with the ancient Greek’s use of ‘muthos’ to describe another way of understanding texts. It’s something like empathy and something like a relationship to meaning which asks not ‘true or false?’ but ‘dead or alive?’ It may not offer the didactic, reasoned lesson of much theological doctrine, but it does offer a way to connect with human religious thinking and feeling. In fact, it’s precisely this feeling that Mach wants to get at: ‘As this project has unfolded I have found my belief in spirit – in the human spirit – reinforced. I’m interested in people – I like them. My work is inhabited by thousands of them going about that very thing – being human.’ (p.15)

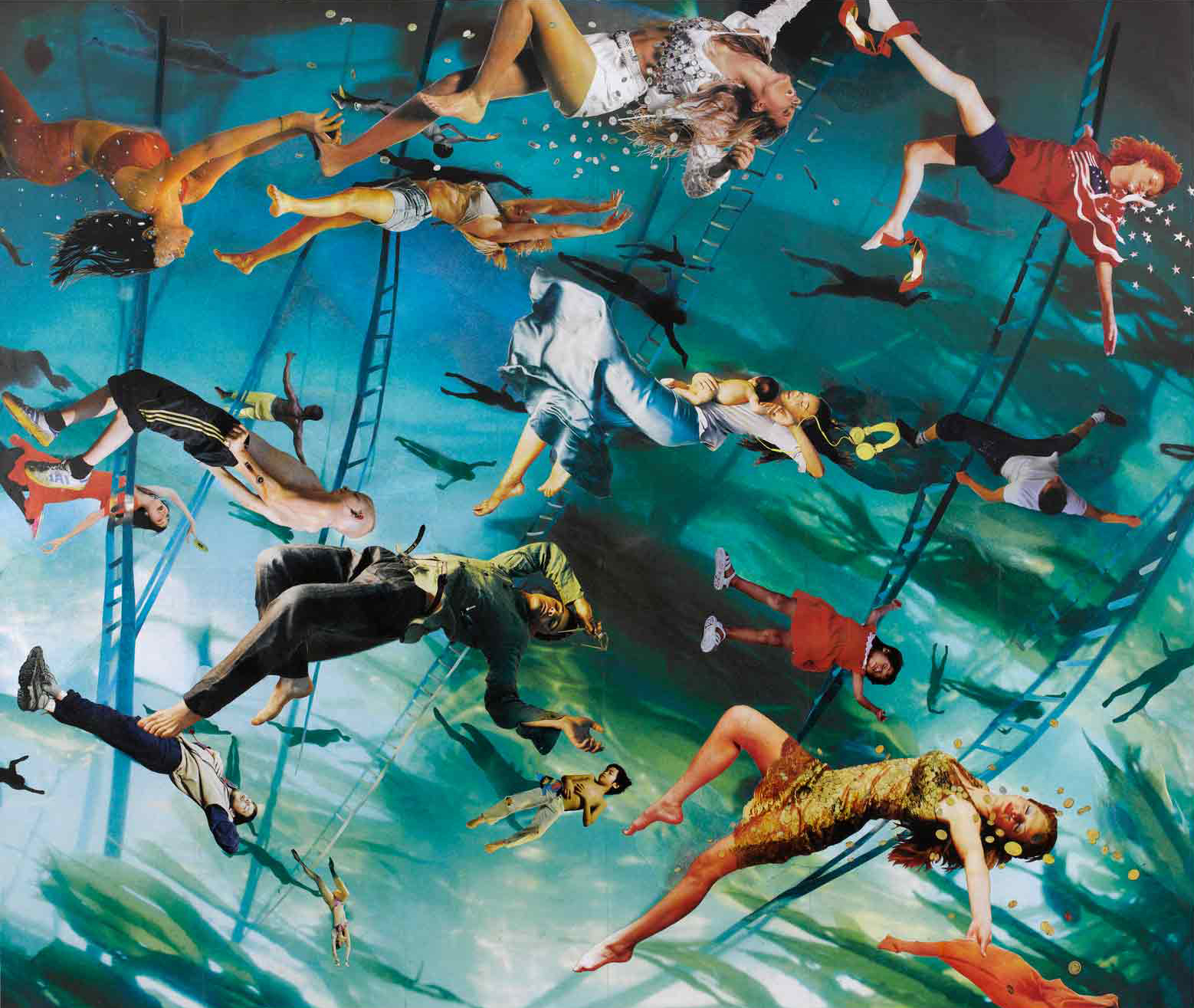

The humanity is what dominates in the collages – figures are part of multitudes featuring every age, colour, expression and dress imaginable, from the crowds around Noah’s ark (in all of the 5 versions) to ‘The Money Lenders’ outside the temple (Sagrada Familia). Even where the scene is more limited, for example ‘Jesus Walking on Water’ or ‘Daniel in the Lion’s Den’ such is the scale from a purely physical point of view (not far off life-size) that the viewer relates even more immediately to what is unfolding in front of them.

The question of engagement is an interesting one, since the ‘spectacle’ of the event might preserve or encourage a remote viewer, as if it were reportage or objective documentary – Mach has himself commented on this media-led view. However, he has also said that the Bible ‘supercharges’ the scenes, which leads to a heightening of the experience of drama. ‘The Last Judgement’ is a particularly engaging triptych, for reflecting a central view in the irises of two eyes shown on either side – even to the extent of suggesting, by allocating left portions of the image in the right eye and vice versa, that we the viewer stand in the same position of what the eyes are seeing. There’s a deliberate encouragement of identification, which perhaps asks too, where might you end up at The Last Judgement – in the chaos and fire, or pillow-fighting in white at the edges?

Also a predominant feature of the collages is the cornucopia effect of multitude and scale, where not just humanity, but the natural and the man-made world overflow like the detritus of materiality. ‘Adam and Eve’ are surrounded by a National Geographic collage which has all the lusciousness of a Damien Hirst spin painting, there are plagues of frogs and locusts, or towers of architecture and storms of confetti-like smoke or paint – in fact in ‘The Last Supper’, created by Mach and his studio team during the show, the pattern on the tablecloth takes off and swirls around the room, adding to the effect of the literally-peeling paint/paper. Mach has in the past worked sculpturally with this information-overload quality of printed media, and here uses it to almost painterly effect. It is like a visual reference to Jean Baudrillard’s hyperreal explosion of representation, and it raises interesting questions for Mach’s biblical subjects – could the hyperreal be read as the supernatural? Does the collapse of material things lead to a revelation of the unseen and the spiritual?

‘Precious Light’ is in the end a fitting title for the show, as are the references to revealed light (Luke 12:2-3 and Matthew 5:14-16) which open the exhibition’s catalogue: there is an uncovering here of biblical subjects and themes which normally hover in the shadows of churches or books rather than art galleries. What has become private isn’t deemed cool enough to be public (or perhaps commercial), and Mach initially found a reluctance on the part of gallery managers to host such work. ‘Cool is for w——‘, as Mach has said, preferring to underline the credibility of pathos in Christian stories and rituals rather than pandering to the approval of arts’ institutions. How refreshing.

David Mach ‘Precious Light’, London: Revolution Editions, 2011.

Jasper Rees ‘David Mach: Why I turned the Crucifixion into Coat Hangers’, The Telegraph online, 11/01/11.

Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin ‘Not all religious art is made by believers’, The Guardian online, 23/09/11.

Header image: Noah’s Ark IV – Edinburgh, 2011, by David Mach, 2011. Used with permission.