This year once again I’m delighted that one of my Advent images, Joseph’s Angel, is being used by Bishop Martin as a Christmas card for the Chichester Diocese. It was originally produced as part of several annual designs, which were initially for personal use, but subsequently became prompts for mini-research projects. Here I reproduce the ideas I explored for another card, The Gift, in 2007. In this card, the opportunity to plumb deeper pictorial traditions comes to the surface, as it was explicitly modelled on the medieval Wilton Diptych, held in the National Gallery’s collection. What follows is a mini-essay I wrote and produced as a miniature booklet at the time, one of my earliest ventures in self-publishing.

A Visual Analysis

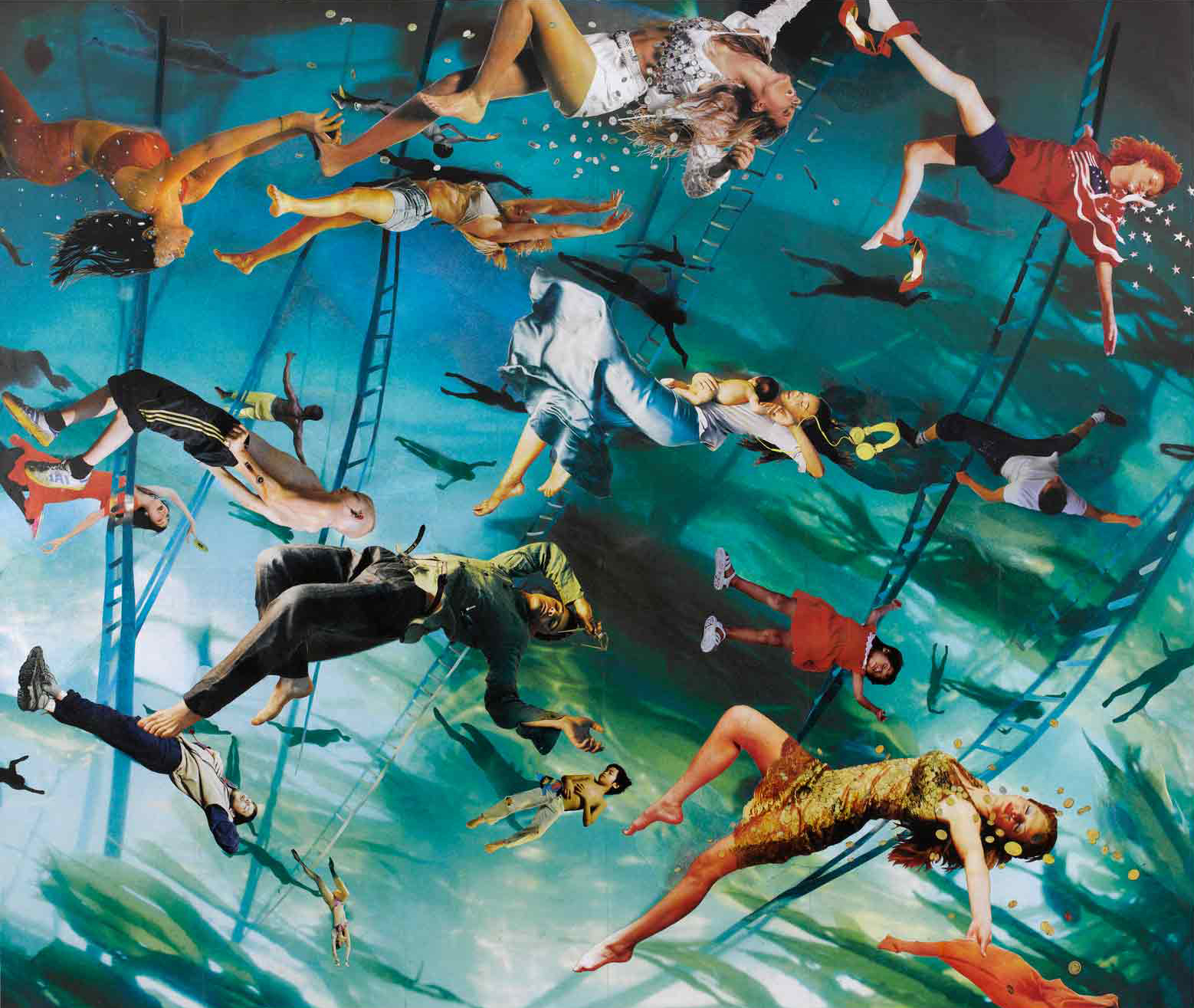

John Drury in his analysis draws out the physicality of the Wilton Diptych in terms of ‘treasure’ (in Painting the Word: Christian Pictures and their Meanings, 2002). My Christmas card is designed in terms of the ‘gift’. ‘Treasure’, in the meaning of the Greek gospels (the Kingdom of Heaven is like treasure), comes from the Greek thesaurus. It specifies a casket or strong-box for valuables – so suggests a container for other riches. ‘Gift’ in our understanding of Christmas presents, also suggests a wrapped container with a present inside. The connotations of both are of something intimately received and delighted in.

At the time it was made, the diptych would have been exclusively enjoyed by one person, King Richard II. He would have held it as a precious object, opening the box on its middle hinge to reveal the glowing gold and blue interior. Essentially, it functioned as ‘a portable altarpiece which could be closed like a book and set up on the altars of different churches and chapels – it was intended for private religious devotion’ (Dillian Gordon, writing for the National Gallery). Gifts at Christmas, if given in the spirit of the wise men, are similarly devotional offerings – they don’t simply meet a need, or fulfill obligation, rather they remind us of another way of living, of another way of loving.

The subject of the painting is designed to encourage such spiritual attentiveness, being as it is a very picture of devotion on the part of the king himself. The picture shows earth and heaven facing each other – on the left hand side, Richard kneels, attended by Saint Edmund, Saint Edward the Confessor and Saint John the Baptist; and on the right the Virgin Mary holds the infant Christ attended by a host of angels. There is a very definite separation of space, whose formality acts on our interpretation of what is going on. It is just such a language of precise arrangement and correlation that I have tried to impose on my Christmas card.

Within the ‘frame’ of the Christmas present depicted, my image is split into four, each part hosting various figures. Drury makes the observation that in the diptych, all eyes on the left look to the right, whereas in heaven, there is a greater containment in some mutual gazes as well as others directed towards earth. My card creates a criss-crossing of gazes, an interaction between angels and humans that is altogether more involved. Mary acknowledges the kings, who both present their gifts and acknowledge the angels, who in turn look down on events and capture the gaze of a shepherd. Joseph by his expression could also be acknowledging everyone.

The exchanges are further added to by a consideration of boundaries. In the diptych, the figures on the left are contained within the frame, and on the right are crowded into it, some not quite making it. In my card, those figures who have appeared on the scene, as it were, stepping in from the outside are the kings and the angels, whose outlines overlap the notional division suggested by the ribbon. They are larger than the other figures, and bring either gifts or a fanfare of announcement. They break into the world of the other pairing, the holy family and the shepherd, whose figures are smaller, more self-contained and stationary.

In terms of background, pattern plays an important part in the diptych, showing a ‘quiet pattern of buds’ on the left, against a ‘bolder and more vibrant pattern, like open leaves or petals’ on the right (Drury). Similarly, flowers on the ground make a fuller, more decorative setting on the right than the bare earth on the left. Whilst I have not exaggerated the use of pattern to distinguish between worlds, the markings of the wrapping paper are stronger on the lower panels of my depicted Christmas present than on those above. This is a simple denotation for ‘groundedness’ which then finds something of a release in the placing of the shepherd on the spiral of ribbon. Here is an abstracted means of lifting a figure both physically and as a reflection of the character’s worship upon the appearance of the angels (at a slight remove from the events below).

The echo of this dimension is also found in the lighter colouring of both angels and sheep. As with the diptych, the angels’ realm is one of concord where similarity of uniform and face (in the medieval tradition of portrait by type rather than studies from life) present overwhelming harmony and affirmation of their thrice-repeated proclamation. Their white robes dominate the image, and as I’ve always thought the animals to be significant witnesses of the Christmas story too, they also pick up this reflection. In the diptych, the prominent animal in the arms of John the Baptist, a lamb, serves a symbolic function in reminding the viewer that Christ was also referred to as the Lamb of God, whose white purity is celebrated in the book of Revelation.

The heart of the diptych links this picture of Christ as a lamb with Christ as triumphant Son of God, since the gesture of the infant is to direct the flag with the red cross to be passed over to the lamb. Here another symbol predominant in painting at the time signifies Christ’s resurrection after death which performed a reconciliation between earth and heaven on account of his perfect sacrifice for the sin of the world. As Drury observes of the diptych, ‘his crossings-over had joined the worlds together’. In my image, there is also a red cross which acts in the same manner to both symbolise and effect a joining of worlds. The message is made clearer in the writing on the gift tag which quotes John 3:16, ‘For God so loved the world, that he gave his only son.’

In the case of the diptych, it is likely that the flag carries multiple meanings as well as that highlighted by Drury, referring to the banner of Saint George, patron saint of England, and also to the kingdom of England as represented in the tiny depiction of an island within the flag’s orb. The presentation of the flag might well refer to the blessing and/or devotion of Richard’s kingdom from/to the Virgin Mary. As also noted by the presence of the king’s personal emblem on the robes of the angels (the white hart brooch), there is a very definite affinity between heaven and earth, sacred and secular. In my card, there is this sense of intermingling since the characters of the nativity are photos of plastic models – mass-produced slightly kitsch figurines employed in the depiction of that most holy night.

Finally, it is the action of the king in the diptych which leads Drury to reaffirming its purpose as an object of devotion – his hands remain open, and he kneels. In ownership of the object itself, Richard is to practice that same reverence and simplicity, so that without grasping or being acquisitive he enters into ‘a moment of happy seeing when the overwhelming beauty of the world beyond breaks into the present’. It is the same with receiving God’s gift of his son, receiving the nativity story again and appreciating the ‘good news of great joy’.

Header image (l-r): The Wilton Diptych, c.1395-9 (used with permission); The Gift, 2007, by Sheona Beaumont.