Lenses and their use pre-Reformation was often considered heretical, whether in camera obscura ‘shows’ (Arnold of Villanova in 1300), Roger Bacon’s ideas, Della Porta on painters’ secret tools. How do you trust something that so distorts plain sight? Hockney says this was actually about power, as wielded by the church. The power over lens-based media reasserted itself in more secular terms with the early 20th-century wars, where Hitler, Stalin and even Mao elevated photo-realism and were suspicious of abstraction.

The revolution in the making and transmission of imagery in recent times is as big as the revolution wrought by printing in conjunction with Renaissance naturalism. Is this good or bad? It has the potential to be both, to huge degrees. Everything from paedophilia to personal understanding, from surveillance and intrusion to the power of the individual over the collective. My fear is that we are not getting a proper cultural grip on all this – that we are stumbling blindly into a blinding glare of ill-understood images, flickering past too rapidly for our critical scrutiny. It’s a big job for the cultural historian. It’s a big job for the artist. We should be in the same base camp, with the same mountain range in sight.

Martin Kemp writing to Hockney, 28/11/99, p.281 in ‘Secret Knowledge’ by Hockney.

The science of photography wasn’t new at the invention of photography (1839), the aesthetics were (attr. Heinrich Schwarz, p.284). = romanticism?

To use a lens-based system involves more than a combination of technical means and an aspiration to naturalism. It involves a conceptual definition of artistic representation as literal imitation, together with a sense that an optical device which creates an image through the geometry of light delivers a more objective picture than the fallible human apparatus. Once this faint in the artificially made image became widespread, it could provide a model for objective naturalism even when not actually used to make a particular work. In this way, it is possible to see the ‘age of the objective image’ as extending from the Renaissance to the present day, with the domain of such images defined as Fine Art until the mid-nineteenth century, when their sovereignty passes to photography and later the cinema and TV.

Martin Kemp to Hockney, 19/01/00, p.284.

The aspiration of optical imitation in Western art is very exceptional. Its apparent ‘normality’ is because of the triumph of this way of representing in our century, above all as the result of the universal spread of photography, film, TV etc.

Martin Kemp to Hockney, 03/03/00, p.286.

Better to have the human hand at work, at least it’s connected to an eye and therefore a body. We are a part of nature, in it, not a mathematical point.

Hockney to Dr Susan Foister, 05/04/00, p.303.

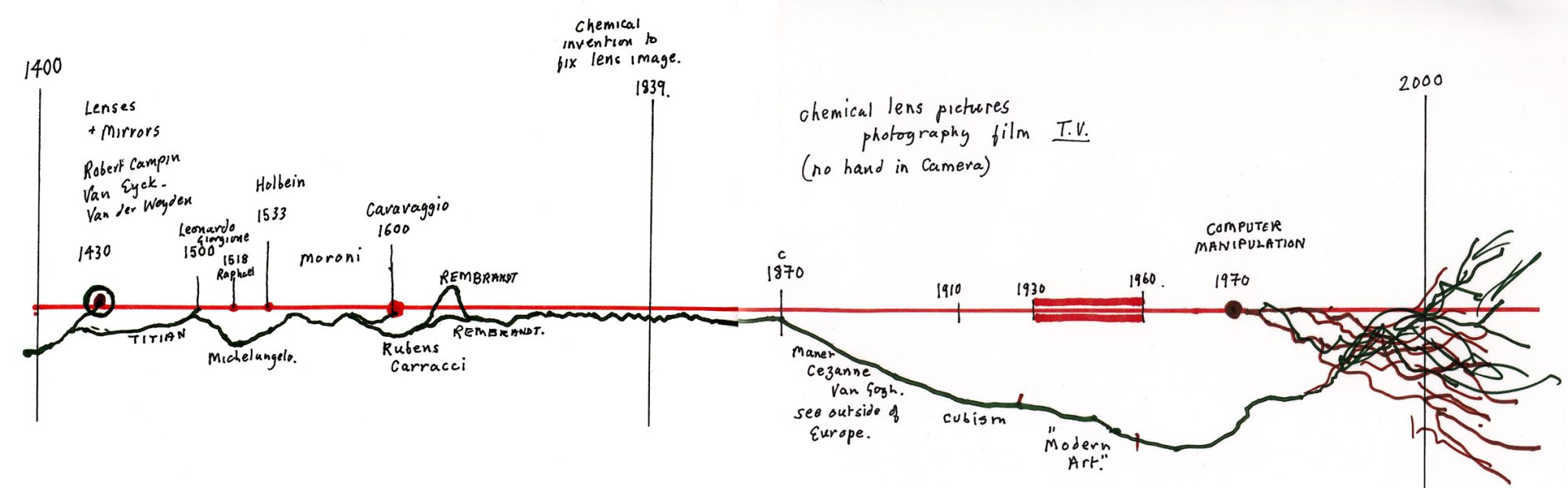

Header image: sketch timeline by David Hockney, in Secret Knowledge (2009).