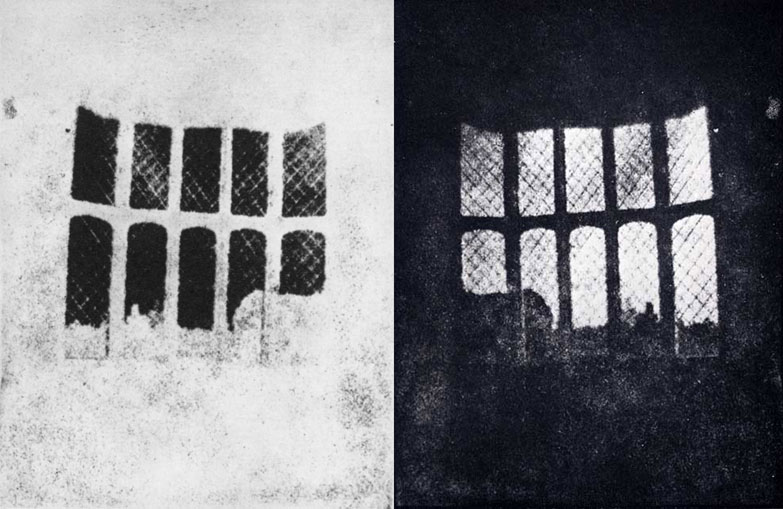

Lent started on the 6th March. I went to an Ash Wednesday service at St Anne’s Bowden Hill (Wilts), got the cross marked on my head and remembered that I am dust. This Lent, I’m putting my foreground research in the background, and committing my time to a church project for Lacock and Bowden Hill. At St. Cyriac’s, Lacock, we’ve taken down all the signs and most of the devotional material – a version of the Lenten practice to cover up all the visual prompts for worship. It’s a way of doing visual theology ‘aniconically’. It’s not that there’s no visual stuff, it’s that the visuality of emptiness or absence is part of the symbolic prompt to self-reflection and penitence. In these windows at St Anne’s, there’s no dominant iconographic programme, and the effect is of slow luminescence, meandering looking, piecemeal symbolic identification, and also reading (above the windows are engraved inscriptions, here ‘Let us not be weary in well doing, for in due season we shall reap if we faint not’). I see it as an invitation to slow down.

The giving of yourself to a new project, to people, to an idea, to a place – is a commitment, a yes to something you have chosen, over other no’s. That involves the path of fidelity, the dying to other options – and it’s a VERY different posture of the heart to the yes-to-everything distracted/rebounding focus of our culture’s invitations to connect and invest. We don’t really move forward by saying yes to everything because we have endless options – we move forward because we said yes to something more singular, and because we said no to other things. The saying no, the stalling/stepping sideways into life’s viscosity looks like hanging backwards, feels like hanging backwards, but it isn’t. In the grace of what time is and of who we are, there is space to recognise that fullness doesn’t need to be hinged to fixation or frenetic activity. The story of history, of wisdom, is always the story of a couple of steps forward, a couple of steps back; it’s always the story of a glimpse of what you could be, and then you head off in that direction, and there are setbacks and you have dark nights of the soul and you wander around the woods and you get lost and then friends become enemies and enemies become friends, because that’s how it works (with thanks to Rob Bell…).

In a previous post, I identified constellations in/with which I work, rather than programmes. Which has the similar sense of allowable ‘drift’ in practice and attention. D’you know what though? It’s really hard. It’s hard in the pressure of our world’s emphasis on efficiency. It’s hard in the self-doubt about wasted time, about ‘indulgence’ when there are ‘better’ things to do, about who cares anyway. If it were a flight from the real, then perhaps these pressures would stick, but actually the point is to distill to a deeper reality. Lent affords the explicit naming of something we instinctively resist: namely that our natural end-point is dust. We don’t ultimately achieve things in our own self-effort, except in Christ’s promise of new life, except in love from without, except in flinging ourselves on God’s meaning and mercy beyond death. Everything we do can become a patient weaving of our heart, body, mind, and soul into this pattern we don’t yet fully see. We don’t see, that’s the point – and we can re-situate our ‘not seeing’ in the promises of Easter’s ‘being seen’. I hope what I’m doing gives itself to that possibility, to a direction of being seen by God, in amidst all the looking and reading that our parish churches (not to mention research in the humanities) invite.

Header image: South windows at St Anne’s Bowden Hill, Wiltshire, 1856. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont.