During the ascent in the balloon at heights of 500 to 1,000 metres over the ground, we were especially enchanted by the shining, full, lush blaze of colours revealed by the earth below us. Far and wide, the forests appeared as the most gleaming, greenest moss or like glorious green velvet. … But as we ascended ever higher in the balloon, the picture changed. Close by, what we first noticed, like in the high mountains, was the blinding, dazzling, cold lighting. … At 4,000 to 5,000 metres above sea level, the earth below us became ever more shrouded in a blue or blue-violet haze.

Swiss geologist Albert Heim, 1912, ‘Luft-Farben’ (literally translated: ‘air-coloured’).

We get to know life under new, unusual, entirely unique conditions – a stimulus that humanity has first begun to taste, and which only a few select are able to enjoy. In good spirits and without will, we follow our wind bride until we again force the balloon to earth with deliberation, calm, and mental presence. All of this gives us nerves of steel for the further battle of daily life, frees our hearts of all of the many little cares and shows us the sublime greatness of nature in proud, lonely flights above a world that is so small.

Austrian balloon pioneer Franz Hinterstoisser, 1904, ‘Aus Meinem Luftschiffertagebuche’.

The landscape in photography became the stage set for a dream dreamt by the middle-class subject who sought to reconstitute him- or herself away from the confines of the city and remote from the masses and the hectic pace of life. In essence, little about this relationship has changed.

Friedrich Tietjen writing in ‘Vanishing Landscapes’, 2008. He suggests the photographers in this book pave a middle way between the ‘moralising tone’ of the glossy landscape photographs in magazines and the intent to aesthetically overwhelm of large-format gallery photographs – here instead ‘these images of vanishing landscapes open up spaces that the observer cannot enter but which remain accessible to our powers of reflection.’

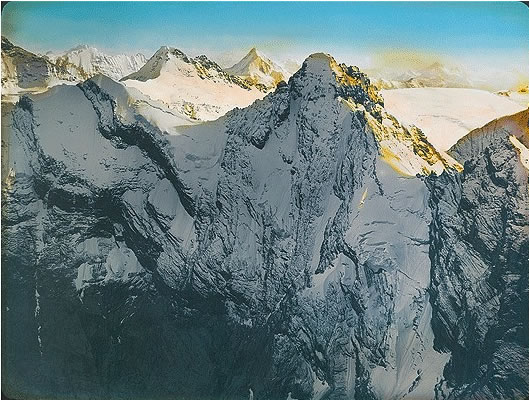

Header image: The Alps, 1910, by Eduard Spelterini.