I’m continuing a blog series which is exploring more experiential ways of engaging with art and theology, with particular reference to photographic technologies. Today, I completed a two-week course from FutureLearn with the University of Edinburgh, ‘Stereoscopy: An Introduction to Victorian Stereo Photography’. Free to access, and wonderfully user-friendly, I checked in over a period of two or three days to whistlestop the 40 or so points on this course. Each was characterised by images, short commentary, links, references, or videos: a byte-sized diet of amuse-bouches on the fascinating technology and contexts of early Victorian stereographs. The online learning platform itself has theological implications for the experience of art and images, though these are not my subject here. Rather, the stereoscope itself is.

They are remarkable images, involving ‘the simultaneous perception of two monocular projections, one on each retina’, as described by Charles Wheatstone in 1838. His invention of the stereoscope created a handheld viewing instrument with mirrors (for drawings in the first instance), but it was the later lenticular stereoscope designed by Sir David Brewster whose lens-based design is remembered. A pair of photographs, each fractionally different as taken from different points, are usually presented together on single cards, which are then inserted like slides a couple of inches in front of the lenses. In my foldable, cardboard ‘readymade’ above, the images are part of the box – a tourist souvenir I picked up at Jumièges Abbey while on holiday in Normandy a few years ago. Optically, the lenses aid the eyes to focus beyond the picture plane, at which point the wall-eyed convergence (as opposed to cross-eyed convergence in front of the picture plane) perceives the images as one, with the illusion of 3D projections across its surface.

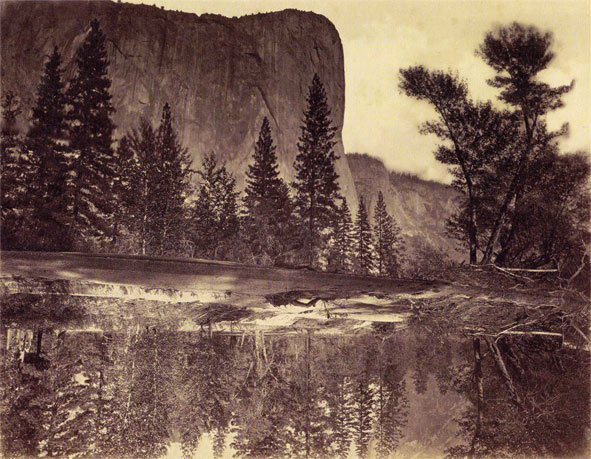

Many a stereoscopic photograph of an abbey ruin was produced during its boom period in the mid-nineteenth century. Roger Fenton (1819-1869) was a master of such views of church architecture. His photographs range from atmospheric ruins in romantic settings (for example those at Furness Abbey, 1860 and Glastonbury Abbey, 1858) to sculptural studies of light and stone detail (for example at Rosslyn Chapel in 1856 and Westminster Abbey in 1858). The ruin carried a pictorial emphasis which imbued typical tourist scenes with an expansive melancholic vision, deliberately evoking the spiritual undertones of the picturesque ideal. Views by Fenton and others such as Francis Frith were readily commercialised by companies specialising in stereographic production, who capitalised on the Victorian appetite for armchair travel. It’s easy today to align the romantic effect with our own somewhat nostalgic attribution to a sentimental style, but the theological weight of a church’s representation should be remembered for carrying some substance at the time. Oliver Wendall Holmes famously evoked what was almost a supernatural experience in looking at stereographs, ‘a dreamlike exaltation of the faculties, a kind of clairvoyance’ (in the 1861 essay, ‘Sun-Painting and Sun-Sculpture’), and he gave specific significance to the Dome of St Paul’s and Canterbury Cathedral, with the presence(s) of divine authentication as amplified by the power of the 3-dimensional lens. The images still hold a certain magic today, and my research will continue to explore the spiritual resonance of looking at, among other things, the Palestinian landscape and Victorian diableries in stereo. It is, specifically, a corporeal and immersive way of seeing, which occasionally received enthusiastic religious attention and explanation.

Header image: Cardboard stereoscope with inbuilt stereoscopic photograph, from Jumièges Abbey, Normandy. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont