The most pressing issue in the photography of place is a site’s history, how it has been affected by time, by climate and by mankind. Landscape photography has become political, not necessarily in terms of environmental causes – although many photographers are directly concerned with such issues – but in terms of the meanings it asks us to consider. Since the 1970s, the best photography of place does not simply expect the viewer to inhabit the depicted space. It asks that the viewer think more deeply about how a place came into being, how environmental and social pressures may change it, and the way people use it. Landscape photography still takes us ‘there’, but the contemporary photographer also recognizes that a place, and its depiction, is a complicated matter – every site is acted upon by both nature and mankind. In photographing place, we are never just photographing nature. We are photographing culture.

Gerry Badger, in The Genius of Photography, p.154.

The heritage industry tends to rely on a kind of freeze-framing of time in order to present the tourist and visitor with a reordered, partial, tidied-up account of what happened at any particular site. Edgelands ruins contain a collage of time, built up in layers of mould and pigeon shit, in the way a groundsel rises through a crack in a concrete floor open to the elements. They turn space inside out, in the way nature makes itself at home indoors, or in the way fly-tipping gathers at their former loading bays, behind obselete walls. Encountering the decay and abandonment of these places is to be made more aware than ever that we are only passing through; that there is something much bigger than us.

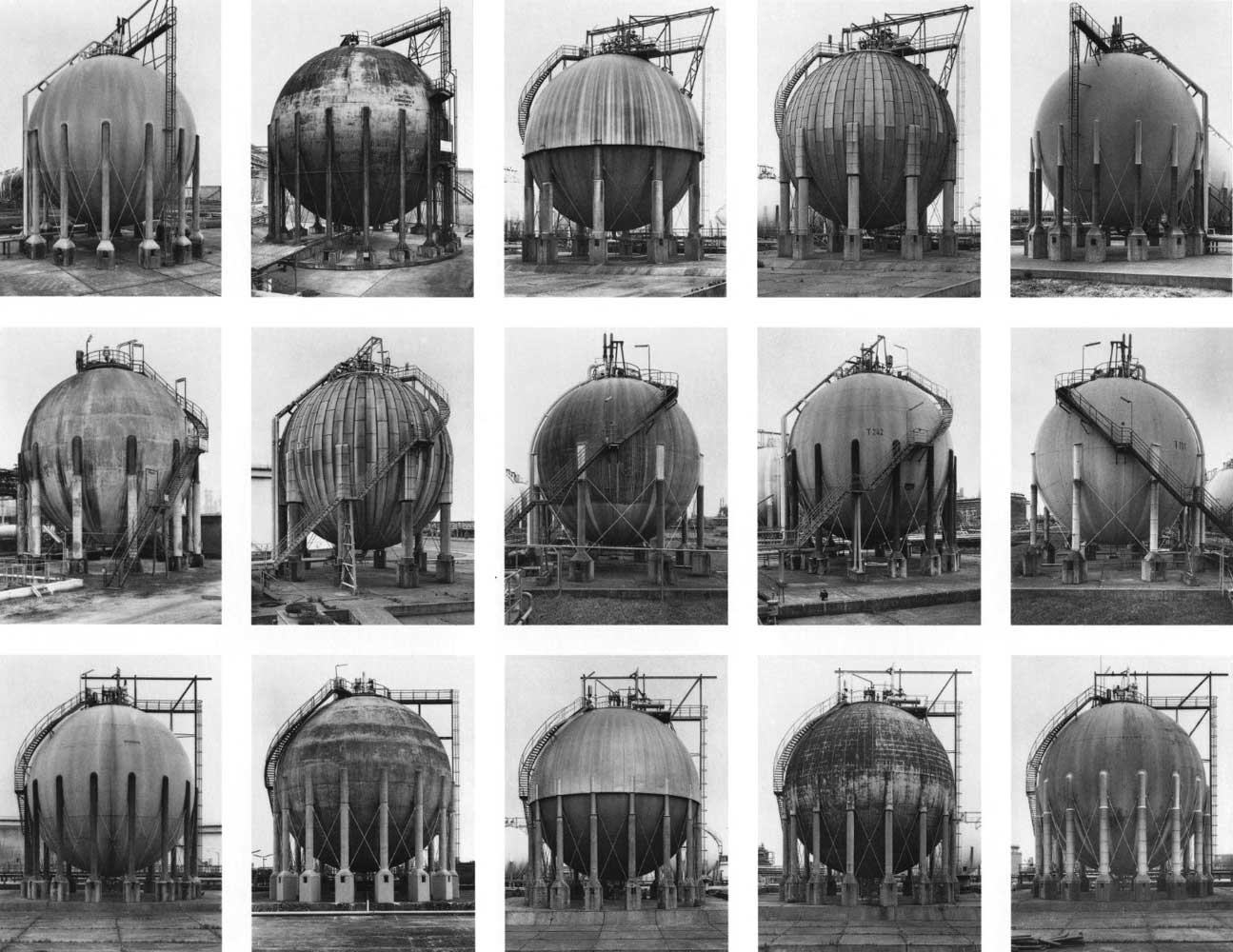

England’s edgelands are the next big thing in photography. After all, photographing gritty urban locations is now likely to lead to arrest on suspicion of planning a terrorist attack, and if you photograph rural Britain you are on very well-trodden ground. This is not to say that edgelands are untouched by the lens. Far from it. Great photographers like William Eggleston and Bernd and Hilla Becher have built their careers on these overlooked landscapes. But their edgelands were in the southern states of America, or in Germany. Eggleston’s notion of the ‘democratic’ function of photography, to step aside from received ideas of what is beautiful or romantic, has influenced a generation of art-school trained photographers. But it has sent most of them into the city. … In the early Seventies, [the Bechers’] attention turned to cooling towers, and they printed the images like sheets from an inventory, nine or ten towers to a page. The effect of this repeated pattern was very powerful. A single cooling tower may look beautiful, but nine cooling towers on one sheet looks like a series of ancient monoliths, or temples, or plinths for statues of long-forgotten gods.

Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts in Edgelands: Journeys into England’s True Wilderness, p.157, 194.

Header image: Spherical Gas Tanks, 1983-92, by Bernd and Hilla Becher.